Getting into medical school is only the first step of an intense journey. Undergoing the admission process and being accepted into medical school can be an exceptional challenge, especially as a student of color, but it isn’t the only hurdle. In a previous blog, I outlined the medical school admission process, its reliance on MCAT scores and key experiences, which are highly influenced by unequally distributed opportunities. I also shared my belief that the current admission process serves to maintain educational injustice and is hindering the diversification of the US physician workforce. There is no easy solution to this issue. Simply admitting more medical students of color, if they are at a different level of readiness for medical school, will not be enough; they must graduate, and medical schools need to be better prepared to support BIPOC students through their medical education.

For context, in 2021-2022, 6.9% of all US allopathic medical school graduates were Black/African American and 6.1% were LatinX.1 According to the most recent diversity data on active physicians provided by the AAMC (2019), only 5% of practicing doctors are Black and 5.8% identified as Hispanic.2 These statistics aren’t anywhere near close to mirroring our U.S. population’s makeup, which is 14.2% Black and 18.7% LatinX.3

Graduation statistics from medical schools follow the same pattern as the MCAT scores – the lower the MCAT score, the lower the graduation rate. For the highest scores (510-528), 91% of students graduated within four years. It starts to drop significantly as the MCAT score decreases, with only 65% of students graduating from medical school in four years who scored between 490-493.4 It stands to reason that if higher numbers of students were admitted with lower MCAT scores, regardless of race or ethnicity, attrition (dropping out) may be higher amongst those with lower MCAT scores. Until the MCAT gap is closed, increasing the representation of diverse students admitted to and graduating from medical school will require healthcare education institutions to meet students where they are.

In my nearly 10 years of working with incredibly diverse medical students, with MCAT scores in the 10th to 50th percentile, I find one consistent, uncomfortable truth. Whatever led to the gap in academic performance on the MCAT did not disappear magically with an acceptance to medical school. The racial gaps in socioeconomic disparities, which are correlated with standardized testing performance before college5 still exist. The lived experiences of racism and their impact on confidence and a sense of belonging, still exist. The pressures of being the exception in your family, your high school, your community, still exist.

What I have come to realize is that graduating diverse doctors requires viewing medical education, much as physicians view health, through a social determinants of learning framework. Similar to each patient having different resources, medical students have different resources, such as levels of self-belief and economic stability. Failing a test or selecting recommended (but not required) resources will be experienced differently by each individual within the cohort. When we consider a policy, a communication, a schedule change, etc. through a social determinant lens, we better understand how to support individual students in ways that matter. By using these determinants as guides, we can tailor how we support students to overcome the social, economic and systemic barriers that otherwise would have removed the access and opportunity they need to succeed in med school.

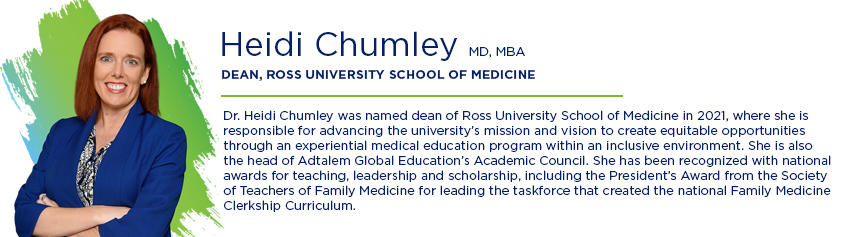

At Ross University School of Medicine, we’re proving this can be done.

In 2022, of the RUSM graduates who attained a residency, 75 were Black/African American and 44 were LatinX. For comparison, 152 US allopathic schools combined graduated 1753 Black and 2232 LatinX physicians, equating to roughly 11 Black and 14 LatinX doctors per medical school.6 We’re still a long way from meeting and exceeding the amount of Black and LatinX representation in the healthcare workforce that mirrors the U.S. population, but through progressive partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs), student support programs, and using the social determinants of learning framework to shape our curriculums, we’re creating pathways for diverse students to get accepted into, thrive in and graduate from our medical school, which then allows them to enter residency programs on their way to becoming practicing physicians.

My hope for the future is to see a healthcare workforce that matches the diversity of the communities it serves. As we continue to push for health equity at RUSM, we also continue to evaluate and reassess our student programs to provide tailored support and help them reach their full potential. I also hope that other medical institutions begin to use social determinants of learning to individualize their education methods so that more Black, LatinX and other students of color can achieve their dreams of becoming doctors.

1 2022 Facts, https://www.aamc.org/media/6121/download?attachment Table B-4.

2 Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019, https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018

4 2023 MCAT Data Selection Guide, https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2022-06/2023%20MCAT%20Data%20Selection%20Guide%20Online.pdf page 33, table 7

5 The Educational Opportunity Monitoring Project: Racial and Ethnic Achievement Gaps (stanford.edu)

6 Table B-6.2: Total Graduates by U.S. MD-Granting Medical School and Race/Ethnicity (Alone or In Combination), 2021-2022 https://www.aamc.org/media/9626/download?attachment