Getting into medical school is arguably the largest barrier to entry into the physician profession, but it’s not the only one. Previously, I covered who gets to succeed in medical school and who gets to graduate. In this article, I look at who gets to be a resident.

After completing medical school, the next step for a graduate is residency—the post-graduate training that every new physician goes through to practice in their medical specialty. Like medical school, the process to get into residency is application-based, expensive, time-consuming, and highly competitive. Also, like medical school, there are significant disparities in how residents are selected. Recent data shows us that graduates who identify as underrepresented in medicine (URIMs) are less likely to progress into residency.

- Just 5.8% of active residents (2020-2021) are Black, 7.8% are Hispanic, 0.6% are American Indian or Alaska Natives, and only 0.2% are Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (AAMC, 2021).

- URIM students are less likely to enter residencies than white students. Black/African American and Hispanic male students are least likely, followed by American Indian/Alaska Native and Hawaiian Native/ Pacific Islander female students (JAMA, 2022).

The residency process is largely accomplished through the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), which uses an electronic application service to funnel tens of thousands of applications to residency programs throughout the United States. Graduates can apply to as many residency programs as they like within their desired specialty.

- In 2022, the average MD graduate submitted 68 applications, leaving residency programs with the lofty task of filtering over a thousand applications per 10 spots.

Programs have few resources to review these increasingly large application pools, leaving them with little option but to screen. Filters like USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK test performance (more on that below) go first, then other criteria like personal experience and medical school emerge as barriers to getting an interview. No interview means no residency and even those who interview aren’t guaranteed to match on their first attempt. In the most unfortunate circumstances, some medical school graduates never match at all or stop applying after their first few attempts.

Another barrier to entering residency is cost. Every program application costs a fee, meaning lower-income students may not apply for as many residency positions. And when an applicant receives an interview, they foot the bill for travel. Things like relocation costs prohibit many graduates from applying to programs outside of their home states or current geographical location. This limits opportunity and bars many students from applying to residencies they’re qualified for but can’t afford.

Sound familiar? It’s a process that mirrors medical school admissions and one that perpetuates an unjust approach of who ultimately enters the medical profession.

The Leaky Pipeline Theory

Traditionally, a point of bias in the residency attainment process has been a student’s USMLE Step 1 test score. In a 2020 study of USMLE Step 1 cutoff scores, URIM students were found to have lower USMLE scores compared to their white counterparts. Because many residency directors historically only interview and accept applicants above a specific score threshold, many URIM students are often denied a seat at the table. This contributes to the “leaky pipeline” theory, where URIM students are removed from the talent pool, which contributes to underrepresentation in the medical field.

In 2021, the USMLE updated Step 1 to remove score reporting and instituted a pass/fail system in its place. However, Step 2 remains the same. It can be inferred that the bias from Step 1 may shift to Step 2.

How the Residency System Fails URIM Physicians

One of the most uncomfortable truths of the residency process is that bias does not stop when a URIM student attains a residency placement.

Black residents report experiencing discrimination and unfair treatment in their programs. In an unpublished study from 2015, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education found that Black physicians made up around 5 percent of all medical residents but represented almost 20 percent of the residents who were dismissed from their programs. A 2020 survey of almost 7,000 surgical residents found that almost 25 percent had experienced discrimination because of their race, ethnicity, or religion, with the highest rates among Black residents (70% reported discrimination), followed by Asian (46%) and Hispanic (25%) residents. This discrimination was also associated with higher rates of burnout and not finishing residency.

Opportunities to Fix the System from the Bottom Up

As healthcare educators, we have a responsibility to change the systemic barriers that keep URIM students from having a seat at the table. First, it’s my recommendation that the MCAT should report scores with recommendations for academic support. For example:

- 40th percentile and higher: Likely to manage academic rigor with little to no support

- 20th – 40th percentile: Able to manage academic rigor but may need learning strategy

- Below 20th percentile: Content support and extended time to master material.

This can serve as a guide for medical education institutions on how to best support incoming students in lower percentiles. Additionally, medical schools should be encouraged to establish their position to specialize in those under the 40th percentile, targeting 50-60 percent of students at that level of preparation and staff accordingly to support them. This way, we can set these students up for better chances of success when they enter the residency MATCH process and begin their residencies.

It’s also my recommendation that the USMLE Step 1 remain pass/fail. This removes the bias based on test scores alone, which can be particularly detrimental to the chances for URIM students. All members of admission committees and residency directors should undergo unconscious bias training, so the ranking process can become fair, just, and equitable.

Finally, as I’ve previously stated in other articles, educators, admission committees and residency directors should take Social Determinants of Learning™ into account when considering potential candidates. The Social Determinants of Learning framework outlines the physical, mental, socioeconomic, and communal barriers to education and reminds us of the challenges our students may face that can adversely affect academic performance. In addition to this outline, it offers guidance on how to provide support to overcome those barriers so students can maximize their potential and achieve better outcomes.

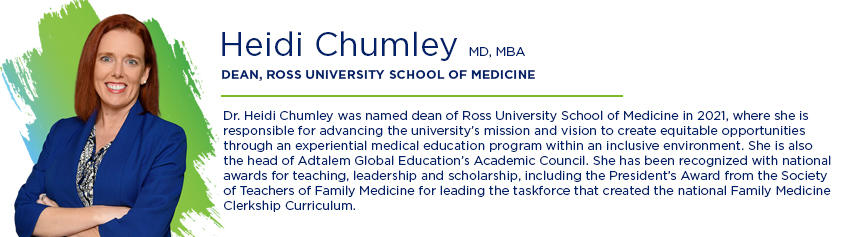

What happens during the MATCH process and in their residencies is largely out of our control. However, it is our responsibility to set our students up for the best chance of success. At Ross University School of Medicine, we’re dedicated to helping our students achieve the best possible outcomes. We were proud to have a 96 percent first-time residency attainment rate in 2022, meaning that 96 percent of our students attaining a 2022-23 residency position out of all graduates or expected graduates in 2021-22 who were active applicants in the 2022 NRMP match or who attained a residency position outside the NRMP. Of the 454 students who attained residencies in 2022, 119 (26%) identified as URIM. I’m also proud to say we have the data that supports our mission to expand access to education and increase diversity in the healthcare workforce, but I still acknowledge that we have a long way to go in order to achieve true and accurate representation in healthcare. At Ross Med, we’ll continue to refine our strategies, increase student support, and keep moving forward until we achieve truly equitable healthcare.